Securing Trust, Enabling Access: A Data Privacy Framework for NIA-User Agency Partnerships in Ghana

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

The National Identification Authority (NIA) is the custodian of Ghana’s most comprehensive national identity dataset. As digital government services mature and interoperability becomes the norm, user agencies such as the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA), banks, telecoms, and insurance companies increasingly rely on NIA’s Identity Verification Services (IVS) for authentication, service delivery, and compliance. However, recent public disputes, such as the GRA-NIA standoff over GH₵376 million in unpaid access fees, expose critical gaps in the legal, technical, and commercial protocols that govern these inter-agency relationships.

This article proposes a resilient and forward-looking contractual framework rooted in Data Protection Act, 2012 (Act 843) and National Identity Register Act, 2008 (Act 750), with a detailed Data Processing Agreement (DPA) at its core. It offers guidance to ensure continuous data access, integrity, safeguards, and enforceable rights for data subjects while maintaining financial sustainability for the NIA.

User Agencies and Data Processing under Act 750

Under Section 75 of Act 750, “user agencies” include any public or private organization approved by the Minister that requires identity data from the NIA. These agencies, which now include the GRA by succession from the Revenue Agencies Governing Board, are entitled to access, use, and retain personal data from the National Identity Register for lawful and specified purposes as outlined in Sections 53 to 56.

However, this access is subject to limits and conditions. The Act mandates the NIA to issue guidelines governing the processing of personal data, including constraints on reuse, requirements for user notification, and strict adherence to purpose limitation. In practice, this means a user agency does not operate as a co-controller but rather functions as a data processor acting under the direction and control of the NIA, which retains the role of primary data controller.

The Need for a Standardised Data Processing Agreement (DPA)

While Act 750 outlines broad duties and entitlements, it lacks the operational detail needed to regulate safeguards, financial terms, and accountability. A comprehensive Data Processing Agreement (DPA) between the NIA and each user agency is therefore essential.

The DPA must clearly define the legal basis and specific purposes for data access, such as taxpayer identification, biometric verification, or Know Your Customer (KYC) compliance. It should list the data types involved—biometric data, identity numbers, and residency status—and describe the nature of processing activities including real-time querying and data retention periods.

Security and confidentiality obligations must be laid out in detail, referencing statutory requirements from Section 47 of Act 750 and Section 28 of Act 843. These include encryption protocols, access management, incident response strategies, and audit trail logging.

Commercial terms should reflect transparent fee structures based on volume, usage, or API calls. Crucially, the DPA should include clauses that prohibit the unilateral suspension of services due to non-payment, instead requiring a defined dispute resolution mechanism and potentially an escrow arrangement or prepayment buffer.

To safeguard data subject rights, the agreement must include mechanisms for handling access requests, rectifications, and cooperation with investigations by the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ). Breach notification timelines should be specified, with liability provisions clearly defining the consequences for unauthorized access, breaches, or misuse.

The DPA should also provide for oversight, giving the NIA the right to audit user agency compliance or require annual reports. Termination clauses must set out the conditions for contract exit and the secure return or destruction of personal data.

III. A Protocol for Sustainable and Secure Data Sharing

Beyond the bilateral DPAs, Ghana needs a national-level Data Sharing and Interoperability Protocol to standardise how user agencies interact with the NIA’s Identity Verification Services. This protocol should be developed collaboratively with stakeholders including the NIA, the Data Protection Commission (DPC), the National Information Technology Agency (NITA), and sector regulators such as the Bank of Ghana, the National Communications Authority, and the GRA.

The protocol must define and operationalise pre-approved data schemas and access models, distinguishing between real-time access (e.g., for border control or SIM registration) and batch access (e.g., for social protection targeting). It should set rules for dispute resolution, including structured escalation pathways such as mediation panels or arbitration options, as well as enforce service level agreements (SLAs) outlining response times, uptime guarantees, and performance benchmarks. This would create a reliable and rules-based data ecosystem.

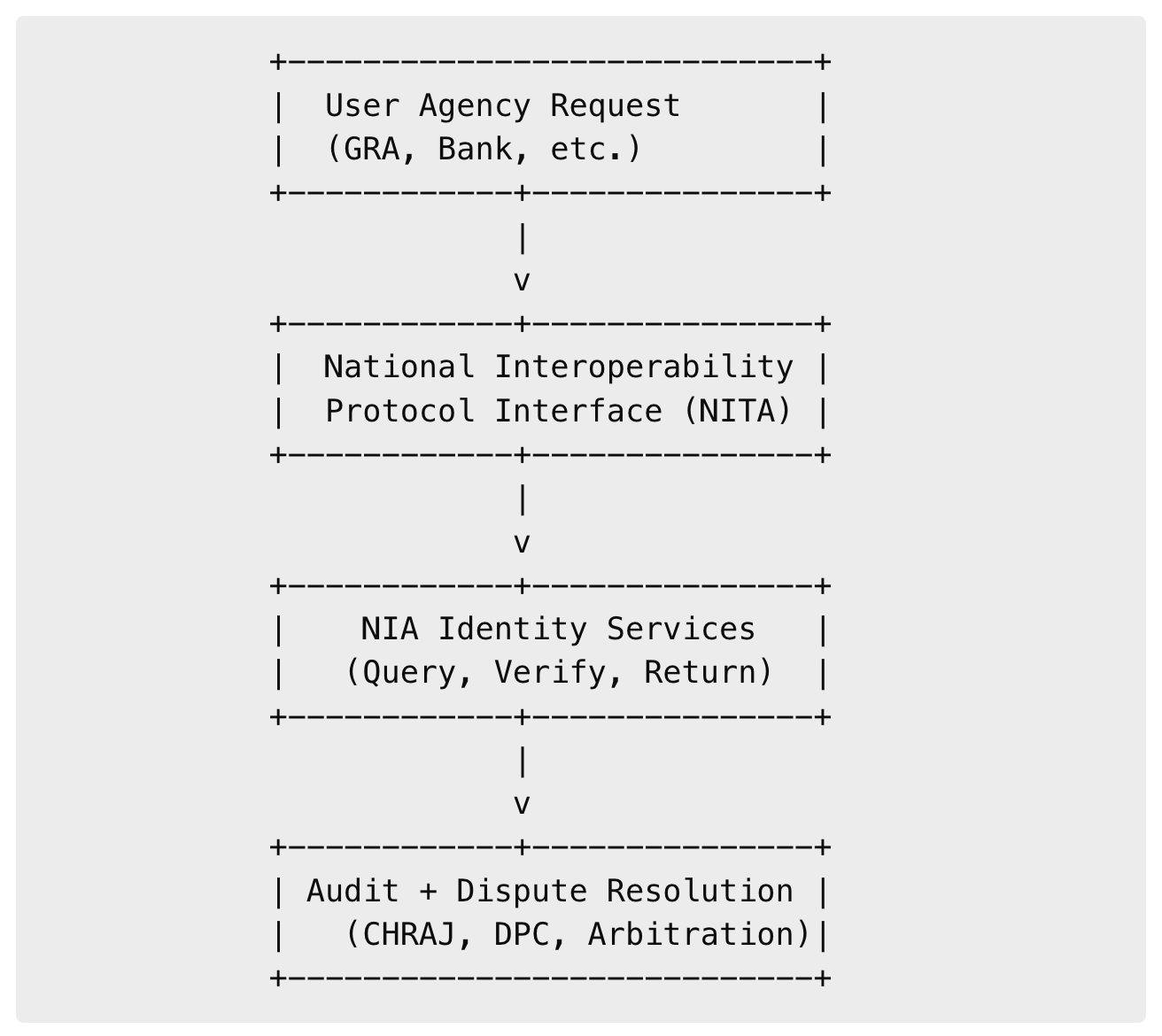

Visual Aid: Embedded Data Sharing Protocol Flow

This visual outlines the embedded flow of a user request moving through a standardised protocol managed by NITA, invoking identity services from the NIA, and concluding with built-in oversight and recourse channels.

The Silent Referee

Despite being the supervisory authority under Act 843, the DPC has been notably absent from public discussions about inter-agency data disputes. This is a missed opportunity. The DPC has both the legal mandate and moral authority to provide oversight in this domain.

It should begin by reviewing and approving DPAs that involve the transfer or processing of sensitive personal data. Moreover, all user agencies and the NIA should be registered data controllers or processors under Act 843. The DPC must also assert its role in ensuring that data subject rights—such as the right to access or correct personal data—are not undermined by operational or commercial disagreements.

Finally, the DPC can develop and enforce sectoral codes of conduct or binding data processing standards. A dedicated Code for Digital Identity Data Use could bring much-needed clarity, consistency, and compliance to the national identity ecosystem.

Avoiding Digital Gridlock

The recent GRA disconnection by the NIA highlights the dangers of treating national identity infrastructure as a transactional utility rather than a critical national resource. The fallout from such interruptions affects not only institutional relationships but also ordinary citizens relying on seamless services at ports, banks, and clinics.

Lessons are clear: data services of this nature should be insulated from fiscal disputes, and no party should have unilateral authority to disrupt access without first exhausting formal resolution pathways. Above all, the rights of data subjects to timely and uninterrupted access to essential services must remain paramount.

Conclusion

Digital identity systems thrive not just on encryption and APIs but on trust. That trust is institutional, legal, and procedural. By embedding detailed, enforceable DPAs within a national data sharing protocol, supervised by the DPC, Ghana can avoid future deadlocks, preserve service delivery, and uphold the privacy rights of its citizens.

In this era of interdependence, the price of poor coordination is not just downtime – it is erosion of public trust.

Author: Desmond Israel, Esq. Partner (Cyberlaw & Technology Practice) AGNOS Legal Company

Comments (4)

Please share your thoughts regarding this blog in the comment section

Kobina Sam

August 8, 2025Very insightful and educative write up.

Desmond Israel

August 8, 2025Thank you for the feedback, glad you find it useful.

Hayford

August 8, 2025I love your final words: In this era of interdependence, the price of poor coordination is not just downtime – it is erosion of public trust

Great insights, Israel!

Desmond Israel

August 8, 2025Thanks Hayford. Consumer and public trust is the currency at the core of data privacy and protection, we can’t miss that.